This is part one of a two-part series.

The Drug Enforcement Administration was established under the Justice Department in 1973 by President Richard Nixon. Its mission was to keep the nation off and away from drugs, which, at least according to the White House, were a moral evil and catalyst of criminal behavior. The agency was formed just two years after Nixon launched what became known as the "war on drugs." Congress and the rest of the nation remained convinced that the scourge of narcotics and drug abusers -- and perhaps particularly those who were young, poor or black -- was pounding at the gates. Over the next four decades, with most drug policy now firmly in the grips of law enforcement officials, the DEA's annual budget saw a fortyfold increase, going from a paltry $75 million to nearly $3 billion in 2014.

With more than 11,000 employees and a host of responsibilities, the agency's activity has expanded worldwide, all the while attracting scrutiny from critics of the drug war who contend that the DEA is an ineffective agency that uses controversial tools to enforce often misguided or unjust federal drug laws.

The catalog of controversies below helps explain why the public has often questioned the DEA's priorities, as well as the methods it employs to advance them. While the DEA does its best to keep many of its dealings out of the public eye -- it regularly claims secrecy is imperative to the success of its anti-drug operations -- here are some of the most sketchy, messed up things that we know it has done:

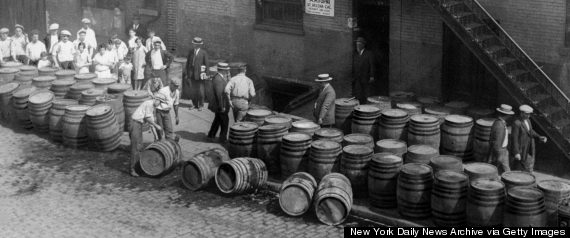

The DEA claimed Prohibition was a success.

![alcohol prohibition officers]()

Most historians believe the "noble experiment" of alcohol prohibition in the 1920s backfired, creating a myriad of negative unintended consequences and serving as a lesson about the hazards of governing public morals. The DEA, however, tells a different story. In 2010, the DEA and the International Association of Chiefs of Police released a report providing key arguments against drug legalization. In one passage, first highlighted by the Republic Report, the report set out to combat what it called the "myth" that "prohibition didn’t work in the 20’s and it doesn’t work now." Its main argument was that the 18th Amendment didn't go far enough to restrict the manufacturing and consumption of alcohol at the onset of Prohibition.

Citing figures that suggest there was a decline in alcohol use during that 13-year period -- statistics that are regularly contested and impossible to verify -- the document argues that Prohibition was a successful policy. The report also downplayed the secondary effects of banning alcohol, such as the precipitous rise of organized crime, at one point suggesting that those effects were increasing before the enactment of Prohibition.

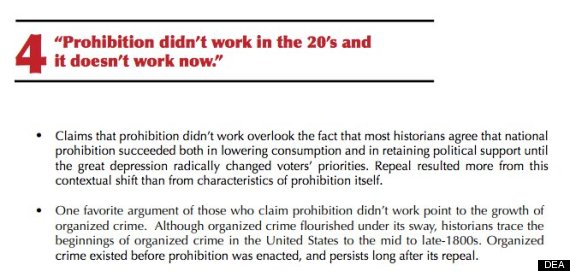

![dea prohibition]()

A sample of the DEA's report.

Unsurprisingly, the report made no mention of the clear negative parallels between early-20th century Prohibition laws and today's laws that target drugs. In both cases, strict prohibition has taken away resources from treatment for addiction and abuse, overburdened court systems and jails, fostered corruption in law enforcement, propped up organized crime and even, some argue, created a damaging disrespect for the rule of law. In return, these incredibly costly enforcement experiments have largely failed to actually limit people's consumptive habits.

The DEA imprisoned an innocent suspect in a holding cell for five days without food or water.

In 2012, 24-year-old Daniel Chong was detained by DEA agents in San Diego after his friend's house was targeted by a drug raid. Chong was told there were no plans to charge him and that he'd be released the same day. But he wasn't released, and agents who heard or saw him over the next five days did nothing, each believing he was somebody else's responsibility. Chong was trapped in a windowless 5-by-10 enclosure without food or water, all for the crime of being in the wrong place at the wrong time. When he was finally discovered, he was incoherent and required medical attention. He said he'd drank his own urine to survive, and at one point attempted suicide. At some point, Chong began to carve "sorry mom" into his arm with broken glass from his eyeglasses, which he ate before being released.

![daniel chong]()

Chong, seen during an interview with NBC San Diego in 2012.

The ordeal ultimately ended in a $4.1 million settlement for Chong. Shortly thereafter, the Justice Department's Office of the Inspector General released a report excoriating top DEA officials not only for the incident itself, but also for failing to immediately report it to their office.

A DEA agent shot himself in a classroom full of children.

Anyone who's spent too much time watching viral videos is familiar with this one:

In April 2004, DEA agent Lee Paige was giving a gun safety demonstration to a classroom full of children when he delivered this now-famous line: "I am the only one in the room professional enough, that I know of, to carry this Glock 40." Moments later, he shot himself in the foot. Rather than take the embarrassing incident in stride (or limp?), Paige eventually sued the DEA, claiming the agency had released the video footage of him. After a prolonged legal battle, he lost the suit.

DEA agents have lost their guns in weird places, including an airport bathroom.

At least Paige knew where his gun was when he shot his foot. An ABC News report in 2008 found that the DEA lost 91 weapons from 2002 to 2007, often in humiliating, or at least seemingly implausible, fashion. Guns were left in supermarkets, at bars, or on top of vehicles; they were stolen from hotel rooms and purses. One "may have fallen into trash basket at work," according to the report. Fighting the war on drugs is apparently not always very precise work.

In 2012, the lapses turned downright dangerous when one DEA agent left his loaded Glock in a crowded airport bathroom beyond the security checkpoint.

A DEA agent left important case documents lying around a suspect's house.

By now we know the DEA has had trouble keeping track of its weapons, and apparently that carelessness also can occasionally extend to physical evidence in the cases it's pursuing. According to a report in the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner earlier this month, an agent accidentally left key documents about a methamphetamine case in the house of a suspect he was arresting. Later, the suspect's father (who was also a suspect in the drug raid) found the documents, which contained information about a confidential DEA informant who had helped build the case. The father angrily contacted the informant, according to reports, and the confrontation eventually led to the father's arrest as well.

While a DEA spokeswoman has since said that the agency is dedicated to its undercover source's "safety and wellbeing," it's obvious that the original agent's negligence put the informant in needless danger.

A DEA agent impersonated a woman by creating a fake Facebook profile in her name.

Earlier this month, BuzzFeed reported on the case of Sondra Arquiett, a 28-year-old New York woman who recently sued the DEA in federal court after an agent impersonated her on Facebook. The agent created an entire fake profile purporting to belong to Arquiett, using personal information and pictures taken from her cell phone following Arquiett's arrest in a cocaine case. He even posted status updates and pictures of her and her children.

The Justice Department defended the sting, through which agents reportedly hoped to extract incriminating information from friends of Arquiett who might be involved with drugs. The Facebook page was eventually taken down, and the Justice Department announced that it was reviewing the tactics. Facebook later told the DEA to stop violating its policies with this bizarre scheme.

Corrupt DEA agents made millions off the drugs they were supposed to be taking off the street.

Giving anybody access to drugs worth millions of dollars can pose problems. But when those same people have spent years familiarizing themselves with networks that know how to turn drugs into profit, there's a clear potential for abuse.

DEA corruption was particularly rampant in the late 1980s. Much of this corruption was run-of-the-mill, such as DEA agents ripping off dealers for cash and drugs, which went largely unreported. But a number of more flamboyant scandals also surfaced, damaging the reputation of the agency.

In one notorious case, DEA agents were caught stealing drugs from the agency's evidence vault. The agents gave the drugs to an informant, who sold them and sent at least $1 million in profits to the agents over five years. Later, the same agents, who reportedly spent this dirty money lavishly, also confessed to stealing bundles of cash from drug busts.

Another case from two decades ago suggests that DEA corruption hasn't always been so blatant. In an undercover money-laundering operation in the 1990s that targeted narco-traffickers in Colombia, corrupt DEA operatives were regularly skimming cash from the pool of money they were supposed to be laundering, according to former agents with knowledge of the case. The agents' actions nearly got an informant killed, according to reports. One agent was found guilty of pocketing $700,000 during the operation and sentenced to two years in jail. He was the only person prosecuted as a result of the failed sting. Bill Conroy of the Narcosphere recently reported that $20 million is still unaccounted for in the case, which remains unresolved.

The DEA has terrorized and killed innocent people.

In 2003, 14-year-old Ashley Villarreal was shot in the head by a DEA agent while driving just blocks away from her San Antonio home. Agents who had been staking out the Villarreal household mistakenly believed the person in the car with the teen was her father, whom they suspected of dealing cocaine. Two days later, Villareal died. A few days after the shooting, Villareal's father was arrested on drug conspiracy charges.

The agents never faced charges in the teen's death, even though testimony from witnesses and subsequent reports conflicted with official accounts of the incident. The details of this case are painful to read, but perhaps most upsetting is the fact that they aren't necessarily unique.

![ashley villarreal]()

Pallbearers carry the casket of Ashley Villarreal following a funeral service. Villarreal, the daughter of a drug suspect, was shot and killed by federal agents. (AP Photo/Eric Gay)

Indeed, Villareal's case is an extreme example of what has become a trend of concerning incidents. As the DEA and other law enforcement agencies have ramped up their use of no-knock raids over the past 25 years, a pattern of disturbing behavior has emerged, with mistakes leading to the injuries and deaths of both civilians and law enforcement. Other times, the damage isn't physical. During a DEA raid in 2007, agents forced their way into a mobile home in California, allegedly shouting obscenities and pointing their guns at the heads of the 11- and 14-year-old girls asleep in the home. The girls were later handcuffed. A few hours later, agents realized they'd ransacked the wrong home. The family later filed a lawsuit claiming the DEA's actions constituted "intentional infliction of emotional distress."

The agency has even killed people on foreign soil.

DEA agents working with local authorities on a Honduran anti-drug mission shot and killed smuggling suspects in two separate incidents over the course of a few weeks in 2012. In both cases, officials claimed the suspects were armed and refusing to surrender, but the episodes nonetheless underscored emerging concerns about the DEA's respect for Honduran sovereignty.

Those killings came just a month after DEA agents took part in an anti-smuggling operation that led to the deaths of four innocent Hondurans, including a pregnant woman. Honduran police initially called the mission a success, but an investigation by journalists and human rights activists later revealed the truth -- the victims of the anti-drug operation that night were on a boat entirely unconnected to the supposed smuggling activity. U.S. officials defended the DEA's involvement, claiming agents didn't fire any rounds during the mission, but the incident sparked aggressive local protests calling for the DEA to leave the area.

Members of Congress later called for a further investigation into the episode and, specifically, the role DEA agents played. But the DEA declined to open an investigation. Months later, reports suggested the agency had not cooperated with local authorities investigating the incident, which led Rep. Hank Johnson (D-Ga.) to ask earlier this year: "Could U.S. agents engaged in the 'war on drugs' abroad operate without any sort of accountability?"

The DEA raided a woman's house because she'd shopped at a garden store.

In 2013, agents raided the Illinois home of Angela Kirking after a trip to a garden store led the DEA to flag her as a potential marijuana grower. Kirking said she'd only purchased fertilizer for her hibiscus plant, but this was enough to get her caught up in an operation that involved monitoring garden stores in search of suspects who might be cultivating marijuana.

The DEA obtained a warrant to investigate Kirking, tracking her electricity consumption and digging through her trash to find a small quantity of marijuana stems. That was apparently enough to authorize a raid. When agents stormed into Kirking's house, they found a small baggie of weed, enough only for a misdemeanor charge.

The DEA once tried to ban pacifiers and glow sticks, claiming they were "drug paraphernalia."

In a prime example of the extreme lengths to which the DEA can go to combat drug use, the agency attempted in 2001 to ban popular symbols of rave culture at a prominent New Orleans club that had become associated with Ecstasy. The American Civil Liberties Union filed a complaint, arguing that items such as masks, glow sticks and pacifiers were not "drug paraphernalia" as the DEA claimed, because they played no part in the actual ingestion of any drugs. A federal judge ultimately barred the DEA from enacting such restrictions, finding that "the government cannot ban inherently legal objects that are used in expressive communication because a few people use the same legal item to enhance the effects of an illegal substance."

![glowsticks]()

The agency is so unwilling to reconsider some of its outdated policies that the DEA chief once refused to acknowledge that marijuana is less harmful than crack and heroin.

For all of the sketchy things the DEA has done while waging the drug war, perhaps most upsetting to critics is the agency's often stubborn insistence that the war should be fought with the same aggressiveness on all fronts.

Earlier this year, the Drug Policy Alliance, an advocacy group dedicated to drug law reform, issued a report showing how the DEA has systematically rejected scientific evidence in order to maintain current prohibitive drug scheduling laws. The report cited a number of cases in which the DEA has undermined, ignored or circumvented research suggesting that marijuana and MDMA, or Ecstasy, don't belong in DEA's Schedule I, a category for substances with no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse or severe psychological or physical dependence.

The agency's unwillingness to reconsider its policies in the face of countervailing scientific evidence was perhaps best demonstrated when DEA Administrator Michele Leonhart testified before Congress in June 2012. In her testimony, Leonhart refused to answer the seemingly straightforward and obvious question of whether heroin or crack are worse for a person's health than marijuana. State and local governments are increasingly acknowledging through policy shifts that marijuana is less harmful than those more potent drugs. But the DEA has insisted on treating marijuana with equal severity. Admitting that it is, in fact, less harmful could have been especially awkward for Leonhart, considering the DEA at the time was in the midst of an aggressive crackdown on medical marijuana facilities.

Raids on legal marijuana facilities have slowed in recent years, and Leonhart's stance on the drug war has appeared increasingly at odds with the more progressive views of Attorney General Eric Holder. Still, the DEA chief recently suggested that the push toward legalization only drives the agency to "fight harder."

![michele leonhart]()

DEA Administrator Michele Leonhart takes part in a news conference at DEA headquarters in Arlington, Va., Thursday, July 26, 2012. (AP Photo/Cliff Owen)

The DEA again showed its rigidity in the drug war earlier this year when Kentucky legalized the cultivation of hemp, a plant that is related to cannabis but lacks the psychoactive ingredient that produces a high. With Kentucky expecting a shipment of 250 pounds of hemp seeds from Italy, the DEA stepped in, impounding the shipment and claiming the importation was still illegal because under current federal drug law, both hemp and cannabis are considered Schedule I substances. After a brief legal battle, the DEA released the shipment.

Be sure to check back soon for part two of this story.

The Drug Enforcement Administration was established under the Justice Department in 1973 by President Richard Nixon. Its mission was to keep the nation off and away from drugs, which, at least according to the White House, were a moral evil and catalyst of criminal behavior. The agency was formed just two years after Nixon launched what became known as the "war on drugs." Congress and the rest of the nation remained convinced that the scourge of narcotics and drug abusers -- and perhaps particularly those who were young, poor or black -- was pounding at the gates. Over the next four decades, with most drug policy now firmly in the grips of law enforcement officials, the DEA's annual budget saw a fortyfold increase, going from a paltry $75 million to nearly $3 billion in 2014.

With more than 11,000 employees and a host of responsibilities, the agency's activity has expanded worldwide, all the while attracting scrutiny from critics of the drug war who contend that the DEA is an ineffective agency that uses controversial tools to enforce often misguided or unjust federal drug laws.

The catalog of controversies below helps explain why the public has often questioned the DEA's priorities, as well as the methods it employs to advance them. While the DEA does its best to keep many of its dealings out of the public eye -- it regularly claims secrecy is imperative to the success of its anti-drug operations -- here are some of the most sketchy, messed up things that we know it has done:

The DEA claimed Prohibition was a success.

Most historians believe the "noble experiment" of alcohol prohibition in the 1920s backfired, creating a myriad of negative unintended consequences and serving as a lesson about the hazards of governing public morals. The DEA, however, tells a different story. In 2010, the DEA and the International Association of Chiefs of Police released a report providing key arguments against drug legalization. In one passage, first highlighted by the Republic Report, the report set out to combat what it called the "myth" that "prohibition didn’t work in the 20’s and it doesn’t work now." Its main argument was that the 18th Amendment didn't go far enough to restrict the manufacturing and consumption of alcohol at the onset of Prohibition.

Citing figures that suggest there was a decline in alcohol use during that 13-year period -- statistics that are regularly contested and impossible to verify -- the document argues that Prohibition was a successful policy. The report also downplayed the secondary effects of banning alcohol, such as the precipitous rise of organized crime, at one point suggesting that those effects were increasing before the enactment of Prohibition.

Unsurprisingly, the report made no mention of the clear negative parallels between early-20th century Prohibition laws and today's laws that target drugs. In both cases, strict prohibition has taken away resources from treatment for addiction and abuse, overburdened court systems and jails, fostered corruption in law enforcement, propped up organized crime and even, some argue, created a damaging disrespect for the rule of law. In return, these incredibly costly enforcement experiments have largely failed to actually limit people's consumptive habits.

The DEA imprisoned an innocent suspect in a holding cell for five days without food or water.

In 2012, 24-year-old Daniel Chong was detained by DEA agents in San Diego after his friend's house was targeted by a drug raid. Chong was told there were no plans to charge him and that he'd be released the same day. But he wasn't released, and agents who heard or saw him over the next five days did nothing, each believing he was somebody else's responsibility. Chong was trapped in a windowless 5-by-10 enclosure without food or water, all for the crime of being in the wrong place at the wrong time. When he was finally discovered, he was incoherent and required medical attention. He said he'd drank his own urine to survive, and at one point attempted suicide. At some point, Chong began to carve "sorry mom" into his arm with broken glass from his eyeglasses, which he ate before being released.

The ordeal ultimately ended in a $4.1 million settlement for Chong. Shortly thereafter, the Justice Department's Office of the Inspector General released a report excoriating top DEA officials not only for the incident itself, but also for failing to immediately report it to their office.

A DEA agent shot himself in a classroom full of children.

Anyone who's spent too much time watching viral videos is familiar with this one:

In April 2004, DEA agent Lee Paige was giving a gun safety demonstration to a classroom full of children when he delivered this now-famous line: "I am the only one in the room professional enough, that I know of, to carry this Glock 40." Moments later, he shot himself in the foot. Rather than take the embarrassing incident in stride (or limp?), Paige eventually sued the DEA, claiming the agency had released the video footage of him. After a prolonged legal battle, he lost the suit.

DEA agents have lost their guns in weird places, including an airport bathroom.

At least Paige knew where his gun was when he shot his foot. An ABC News report in 2008 found that the DEA lost 91 weapons from 2002 to 2007, often in humiliating, or at least seemingly implausible, fashion. Guns were left in supermarkets, at bars, or on top of vehicles; they were stolen from hotel rooms and purses. One "may have fallen into trash basket at work," according to the report. Fighting the war on drugs is apparently not always very precise work.

In 2012, the lapses turned downright dangerous when one DEA agent left his loaded Glock in a crowded airport bathroom beyond the security checkpoint.

A DEA agent left important case documents lying around a suspect's house.

By now we know the DEA has had trouble keeping track of its weapons, and apparently that carelessness also can occasionally extend to physical evidence in the cases it's pursuing. According to a report in the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner earlier this month, an agent accidentally left key documents about a methamphetamine case in the house of a suspect he was arresting. Later, the suspect's father (who was also a suspect in the drug raid) found the documents, which contained information about a confidential DEA informant who had helped build the case. The father angrily contacted the informant, according to reports, and the confrontation eventually led to the father's arrest as well.

While a DEA spokeswoman has since said that the agency is dedicated to its undercover source's "safety and wellbeing," it's obvious that the original agent's negligence put the informant in needless danger.

A DEA agent impersonated a woman by creating a fake Facebook profile in her name.

Earlier this month, BuzzFeed reported on the case of Sondra Arquiett, a 28-year-old New York woman who recently sued the DEA in federal court after an agent impersonated her on Facebook. The agent created an entire fake profile purporting to belong to Arquiett, using personal information and pictures taken from her cell phone following Arquiett's arrest in a cocaine case. He even posted status updates and pictures of her and her children.

The Justice Department defended the sting, through which agents reportedly hoped to extract incriminating information from friends of Arquiett who might be involved with drugs. The Facebook page was eventually taken down, and the Justice Department announced that it was reviewing the tactics. Facebook later told the DEA to stop violating its policies with this bizarre scheme.

Corrupt DEA agents made millions off the drugs they were supposed to be taking off the street.

Giving anybody access to drugs worth millions of dollars can pose problems. But when those same people have spent years familiarizing themselves with networks that know how to turn drugs into profit, there's a clear potential for abuse.

DEA corruption was particularly rampant in the late 1980s. Much of this corruption was run-of-the-mill, such as DEA agents ripping off dealers for cash and drugs, which went largely unreported. But a number of more flamboyant scandals also surfaced, damaging the reputation of the agency.

In one notorious case, DEA agents were caught stealing drugs from the agency's evidence vault. The agents gave the drugs to an informant, who sold them and sent at least $1 million in profits to the agents over five years. Later, the same agents, who reportedly spent this dirty money lavishly, also confessed to stealing bundles of cash from drug busts.

Another case from two decades ago suggests that DEA corruption hasn't always been so blatant. In an undercover money-laundering operation in the 1990s that targeted narco-traffickers in Colombia, corrupt DEA operatives were regularly skimming cash from the pool of money they were supposed to be laundering, according to former agents with knowledge of the case. The agents' actions nearly got an informant killed, according to reports. One agent was found guilty of pocketing $700,000 during the operation and sentenced to two years in jail. He was the only person prosecuted as a result of the failed sting. Bill Conroy of the Narcosphere recently reported that $20 million is still unaccounted for in the case, which remains unresolved.

The DEA has terrorized and killed innocent people.

In 2003, 14-year-old Ashley Villarreal was shot in the head by a DEA agent while driving just blocks away from her San Antonio home. Agents who had been staking out the Villarreal household mistakenly believed the person in the car with the teen was her father, whom they suspected of dealing cocaine. Two days later, Villareal died. A few days after the shooting, Villareal's father was arrested on drug conspiracy charges.

The agents never faced charges in the teen's death, even though testimony from witnesses and subsequent reports conflicted with official accounts of the incident. The details of this case are painful to read, but perhaps most upsetting is the fact that they aren't necessarily unique.

Indeed, Villareal's case is an extreme example of what has become a trend of concerning incidents. As the DEA and other law enforcement agencies have ramped up their use of no-knock raids over the past 25 years, a pattern of disturbing behavior has emerged, with mistakes leading to the injuries and deaths of both civilians and law enforcement. Other times, the damage isn't physical. During a DEA raid in 2007, agents forced their way into a mobile home in California, allegedly shouting obscenities and pointing their guns at the heads of the 11- and 14-year-old girls asleep in the home. The girls were later handcuffed. A few hours later, agents realized they'd ransacked the wrong home. The family later filed a lawsuit claiming the DEA's actions constituted "intentional infliction of emotional distress."

The agency has even killed people on foreign soil.

DEA agents working with local authorities on a Honduran anti-drug mission shot and killed smuggling suspects in two separate incidents over the course of a few weeks in 2012. In both cases, officials claimed the suspects were armed and refusing to surrender, but the episodes nonetheless underscored emerging concerns about the DEA's respect for Honduran sovereignty.

Those killings came just a month after DEA agents took part in an anti-smuggling operation that led to the deaths of four innocent Hondurans, including a pregnant woman. Honduran police initially called the mission a success, but an investigation by journalists and human rights activists later revealed the truth -- the victims of the anti-drug operation that night were on a boat entirely unconnected to the supposed smuggling activity. U.S. officials defended the DEA's involvement, claiming agents didn't fire any rounds during the mission, but the incident sparked aggressive local protests calling for the DEA to leave the area.

Members of Congress later called for a further investigation into the episode and, specifically, the role DEA agents played. But the DEA declined to open an investigation. Months later, reports suggested the agency had not cooperated with local authorities investigating the incident, which led Rep. Hank Johnson (D-Ga.) to ask earlier this year: "Could U.S. agents engaged in the 'war on drugs' abroad operate without any sort of accountability?"

The DEA raided a woman's house because she'd shopped at a garden store.

In 2013, agents raided the Illinois home of Angela Kirking after a trip to a garden store led the DEA to flag her as a potential marijuana grower. Kirking said she'd only purchased fertilizer for her hibiscus plant, but this was enough to get her caught up in an operation that involved monitoring garden stores in search of suspects who might be cultivating marijuana.

The DEA obtained a warrant to investigate Kirking, tracking her electricity consumption and digging through her trash to find a small quantity of marijuana stems. That was apparently enough to authorize a raid. When agents stormed into Kirking's house, they found a small baggie of weed, enough only for a misdemeanor charge.

The DEA once tried to ban pacifiers and glow sticks, claiming they were "drug paraphernalia."

In a prime example of the extreme lengths to which the DEA can go to combat drug use, the agency attempted in 2001 to ban popular symbols of rave culture at a prominent New Orleans club that had become associated with Ecstasy. The American Civil Liberties Union filed a complaint, arguing that items such as masks, glow sticks and pacifiers were not "drug paraphernalia" as the DEA claimed, because they played no part in the actual ingestion of any drugs. A federal judge ultimately barred the DEA from enacting such restrictions, finding that "the government cannot ban inherently legal objects that are used in expressive communication because a few people use the same legal item to enhance the effects of an illegal substance."

The agency is so unwilling to reconsider some of its outdated policies that the DEA chief once refused to acknowledge that marijuana is less harmful than crack and heroin.

For all of the sketchy things the DEA has done while waging the drug war, perhaps most upsetting to critics is the agency's often stubborn insistence that the war should be fought with the same aggressiveness on all fronts.

Earlier this year, the Drug Policy Alliance, an advocacy group dedicated to drug law reform, issued a report showing how the DEA has systematically rejected scientific evidence in order to maintain current prohibitive drug scheduling laws. The report cited a number of cases in which the DEA has undermined, ignored or circumvented research suggesting that marijuana and MDMA, or Ecstasy, don't belong in DEA's Schedule I, a category for substances with no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse or severe psychological or physical dependence.

The agency's unwillingness to reconsider its policies in the face of countervailing scientific evidence was perhaps best demonstrated when DEA Administrator Michele Leonhart testified before Congress in June 2012. In her testimony, Leonhart refused to answer the seemingly straightforward and obvious question of whether heroin or crack are worse for a person's health than marijuana. State and local governments are increasingly acknowledging through policy shifts that marijuana is less harmful than those more potent drugs. But the DEA has insisted on treating marijuana with equal severity. Admitting that it is, in fact, less harmful could have been especially awkward for Leonhart, considering the DEA at the time was in the midst of an aggressive crackdown on medical marijuana facilities.

Raids on legal marijuana facilities have slowed in recent years, and Leonhart's stance on the drug war has appeared increasingly at odds with the more progressive views of Attorney General Eric Holder. Still, the DEA chief recently suggested that the push toward legalization only drives the agency to "fight harder."

The DEA again showed its rigidity in the drug war earlier this year when Kentucky legalized the cultivation of hemp, a plant that is related to cannabis but lacks the psychoactive ingredient that produces a high. With Kentucky expecting a shipment of 250 pounds of hemp seeds from Italy, the DEA stepped in, impounding the shipment and claiming the importation was still illegal because under current federal drug law, both hemp and cannabis are considered Schedule I substances. After a brief legal battle, the DEA released the shipment.

Be sure to check back soon for part two of this story.